Amazon upgraded warehouse AC system after saying worker’s death wasn’t heat-related

Amazon upgraded the air conditioning system at a New Jersey warehouse where it blamed a worker’s death during a heat wave last month on a “personal medical condition,” according to three facility employees and photographs seen by NBC News.

One photo shows a large new ducting system installed on a ground floor of the warehouse in Carteret, known as EWR9, with the ducts pointing upward.

Workers said the equipment was part of a new industrial air conditioner that the company added weeks after the death of Rafael Reynaldo Mota Frias, a 42-year-old Dominican national, in mid-July. It wasn’t clear if the system was up and running yet.

Employees also said more fans had been installed around the warehouse in recent weeks. The area where Frias was working when he collapsed was known to be especially hot and with little air circulation, according to seven workers at the site.

Amazon said it regularly updates its facilities. “Our climate control systems constantly measure the temperature in our buildings, and our safety teams are empowered to take action to address any temperature-related issues,” said spokesman Sam Stephenson. He said the company takes safety precautions in warm weather, always provides access to water stations — not just on hot days — and encourages employees to take breaks to hydrate.

Amazon and other major logistics operators, including UPS and FedEx, have faced growing scrutiny around labor conditions amid a summer of record heat across the country. The high temperatures have raised concerns about the safety of warehouse employees, delivery drivers and others who work outdoors or in large industrial spaces during hot weather. Dozens of workers at an Amazon air hub in San Bernardino, California, staged a walkout last weekciting heat-related job risks among other complaints.

This summer, after years of reports about injuries at Amazon facilitiesfederal authorities led by the US attorney’s office in Manhattan opened an investigation into the company’s warehouses, soliciting information from workers, supervisors and others about conditions there.

Staffers at the Carteret fulfillment center have said that managers began handling out more water and snacks and encouraging workers to take breaks after Frias’ death, which triggered anger and questions within the EWR9 workforce.

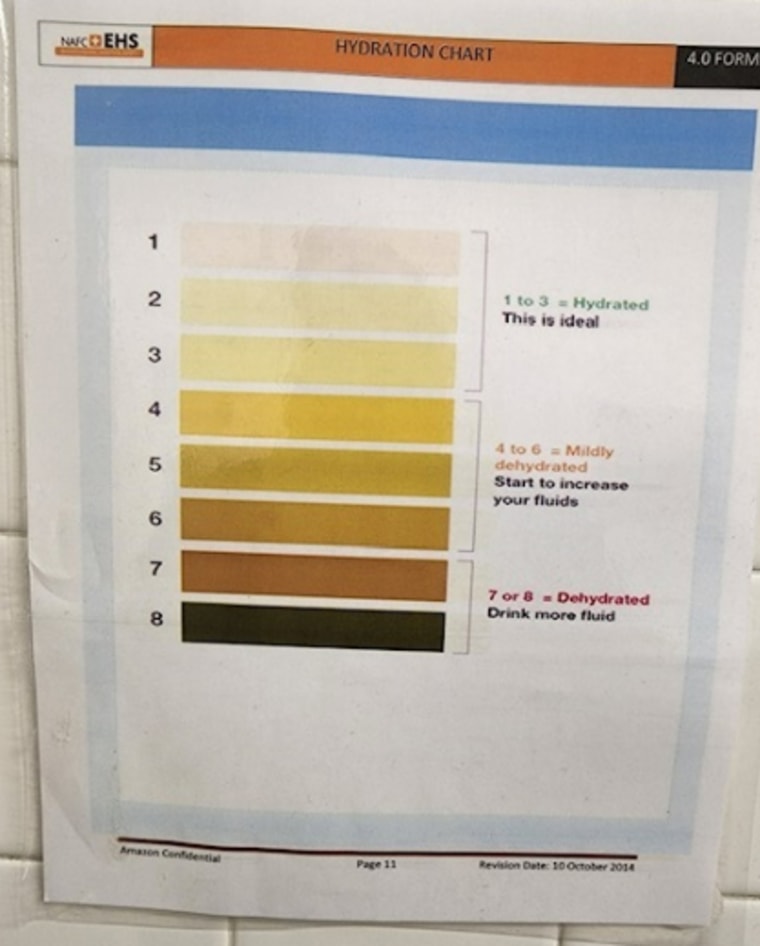

Management posted charts showing dehydration risks indicated by urine color in some of the facility’s bathrooms after the worker died, according to one EWR9 employee and a photo of the chart. Amazon didn’t immediately comment on the bathroom notices.

“Amazon is an agency that reacts to situations. They’re not proactive,” said the employee, who asked not to be identified for fear of reprisal. “They wait till something happens and then they act like they’re doing something.”

The staffer said managers made sure that there were fans at every workstation after Frias’ death, but that parts of the warehouse with little cool air remained very hot.

“Prior to him passing away, every station didn’t have a fan,” the employee said. “It’s hot inside a warehouse, and then you have a fan blowing hot air on you.”

Frias died after collapsing around 8 am on July 13 during the busy Prime Day shopping rush, which coincided with an East Coast heat wave that drove outdoor temperatures in the Carteret area into the low 90s. Facility workers and Amazon Labor Union President Chris Smalls have said they believe the heat was a factor, alleging that Frias had been kept working despite flagging to management that he was having chest pains.

Amazon has dismissed that characterization of events. Stephenson referred to the company’s statement last month, which disputed “rumors” surrounding Frias’ death and said an internal investigation had determined it “was related to a personal medical condition.”

The death kicked off an investigation by federal regulators with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which has since opened another inquiry into two additional deaths of people employed at a separate Amazon facility in New Jersey. One of those stemmed from a fall from a ladder, according to police cited in local news reports, while details around the other death are less clear. OSHA confirmed the probes are ongoing and declined to comment further. Amazon has said it is cooperating with investigating authorities.

The workplace-safety agency, which is operated by the Labor Department, says that heat is a “growing problem” threatening workers across the country. OSHA has put the creation of a heat-related workplace rule on its official agenda, and labor advocates are pushing for such a federal standard. At least four states — California, Minnesota, Oregon and Washington — have rules on the books governing high heat in workplaces, and legislators in other states are considering similar policies.

At the EWR9 warehouse, employees said the atmosphere changed temporarily following the worker’s death, as managers seemed to soften up a bit, before getting stricter recently. Some workers said they believed that firings over small infractions were occurring more frequently and that management had imposed tighter rules in some areas, like preventing workers from using their phones at their stations, even to listen to music.

Sequoya Guyden said she was fired at the beginning of August, after missing a few days of work when her car broke down during her lunch break. Amazon workers are allotted a limited amount of unpaid time off, and Guyden said her balance had been low.

She said she tried to make her case to the company, even submitting documentation about her car’s repair. But after trying to address the issue with an HR representative, she says, the discussion became heated and she was advised that she should’ve walked to work or taken a cab.

Upon terminating her, Amazon told Guyden in an email that she hadn’t provided the right documentation. She tried to appeal the decision but was told in a follow-up email that her firing was upheld. Both emails, viewed by NBC News, were signed “EWR9 HR” rather than with a manager’s name.

Guyden says she was retaliated against for pushing back during her conversation with the human resources employee.

“I feel like it was personal stuff — the confrontation between me and HR,” said Guyden, who moved to New Jersey year and a half ago to take the job at Amazon. “I came here from Louisiana to do something new. I think it’s a foul.”

Stephenson said that Guyden was fired “for having negative unpaid time off after exhausting all of her time off options” and that she didn’t appeal the decision when given an opportunity.

After NBC News contacted Amazon about Guyden’s case, she received another email from EWR9 HR on Friday, saying she could appeal by phone on Monday morning at 8 am and acknowledging a “miscommunication” in the matter.

Guyden said she is starting a new job this week and is no longer interested in working for Amazon.

“I shouldn’t have to go through that at all,” she said. “I got four kids and I’m a single mom. Kids have had to watch me budget and penny pinch. … Me going back to work in [Amazon’s] chaos won’t better my situation.”